Light Up Your Grieving Heart.

{source}

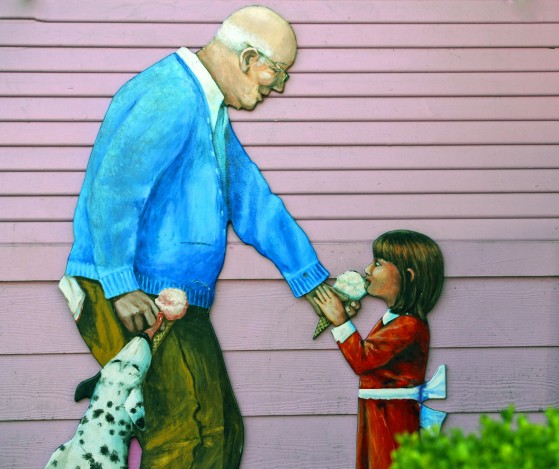

We are walking hand in hand, my little legs pumping to keep up with his.

“How fast can you go? Show me how fast we can go.”

He liked to walk fast; New Yorkers walk fast, they just do. I am counting cracks in the sidewalk and hopping over them just like the rhyme says to do.

We make a right, and head up the hill, cut through the blacktop parking lot of some fast food joint long since turned into something else, and enter the drugstore. I still have the scent of that store in my nostrils, and it hasn’t changed in 20 years.

That musty-air-condition/carpet-pressed-with-the-stale-scent-of-nicotine smell. I’m picking out stickers in the aisle and sticker books to put them in. I’m in the aisle with the marble Mead notebooks.

I have always adored those college-bound pages; blue lines, red column. Empty; fresh like a new beginning. All those notebooks in every store I go to; my new beginning, my soul being called out to spill its stardust contents in black ink. And he never denied me those notebooks.

Anywhere we went, he never denied me a thing. Oh, he would tell me, “Now, Alise, I can’t get you anything today, okay?” and I’d say, “Okay, grandpa,” as we went up the street to Miggy’s grocery store.

Walk through the automatic doors as they slid open, and he’d grab the Staten Island Advance, smile as all the people said Hello to Miggy and his granddaughter, especially the neighbor girl, Nicole Lucatorto’s sister, Christine.

I’d ask politely for something and she’d swipe it down the conveyor belt. Stickers, Raisinets, ice cream, notebooks, crayons, books. My grandpa would get it anyway. My grandpa fed my creativity with the vessels designed to hold it.

Who would I have become if he had not? Would I still love to draw and paint and write if he didn’t buy those simplest of things? He fed the growing writer her sustenance, treated me to happy meals. Let me play with sparklers, and I had my very first magic wand before I saw the magic of a pencil and a pen.

We walked up the street to Clove Lake Park, and I learned how to fly on those hot rubber swings on the steaming blacktop. I was a little girl with her grandpa, exploring a vast green world that looked so big. Suddenly it looks so small, when did I get bigger? When did you get so frail?

I miss the dinners you cooked, ditalini pasta with the meat sauce, parmesan melted on top. I miss going to sleep to all your friends laughing in the kitchen while you all played cards.

You’d recite the rosary in the bathroom after you washed up. I’m sorry now that my faith could never be the kind reliant on those rosary beads, a head held bowed inside four stuffy walls on a hard bench when I’d rather be outside.

Even at your funeral mass, I would have preferred to be outside where I could feel the sun on my face and the wind in my hair, sink my toes into the soil we’ll all be a part of again.

I would have cried freer, knowing the tears are the salt made from the oceans inside of me. Oh, how I longed at that moment to be by the sea. To be on vacation in Atlantic City with you racing through casino floors the security guards said children weren’t allowed on. You let us play the slot machines.

I wish we could play blackjack right now. I wish I was spending summer days in the backyard, picking cherry tomatoes and string beans with you, eating them all before they made it into the house. I am four again, not 24, and all I want to see is the smile in your eyes, not the pixels on my computer screen.

I want to hold your hand again, why are my hands always cold? That’s not you up there, lying there. That’s not you.

I can hear your voice say my name as you walk down the hall into the kitchen to fix a bowl of Cheerios, cut up a banana for me and you, as I pick up the phone to tell you about my days, so vivid it echoes.

These are just some of the shooting star memories rocketing off inside my head, bouncing around in my brain like the atoms of a nucleus.

So many memories, and I’m left thinking that people fear death not because of the unknown they’ll pass into, but because of the cold marble mortality that glares at them after each opportunity to live they turn down for fear of those opportunities’ outcomes.

The memories we could be making we just let pass because we are baby birds afraid to leap and learn how to spread our wings and soar. We fear the life we could be leading, and that is why we are so afraid of its end.

“If you don’t try to fly, and so break yourself apart, you will be broken open by death, when it’s too late for all you could become.” ~ Rumi

My grandpa was not afraid to fly. My grandpa knew how to live. My grandpa taught me how to make so many memories. He said, “Life is for the living.”

How many of the living are even truly alive?

I have been broken open.

I will not sit scared in my bird nest; I will thrust forward toward the sky. I will aim higher than the rising sun on the horizon line; I will take every leap, every time.